Time Magazine recently ran an article encouraging readers to think of airports as small cities. From Beijing to Dubai, the last decade or two has seen mammoth new airports built in expectant hotspots. (Although the US has generally lagged in building new airports or rehabilitating older ones, part of our multi-generational failure to invest in our own infrastructure.) Airplane orders are sometimes looked at as a sign of economic health, given the average cost per passenger jet (upwards of $300 million for a Boeing 747) and the broad supply chain of manufacturing needs and services that go into building each one. Orders are up so recent indicators suggest that, indeed, things are improving in our economy.

All of this was on my mind a couple weeks ago as I sat with a colleague at the airport in Buffalo, New York, waiting for my flight back to JFK. Before you jump to the wrong conclusions, the fault this time was not with the airline (JetBlue, which was generally strong on service and on its communication around the delays) or with weather in Buffalo. It was raining and windy in New York, and JFK was suffering from a range of unspecified delays, which meant that my 6:30pm flight didn’t leave until 11pm, and didn’t land until 1:30am. The only good thing about the situation was that flying into JFK meant we were able to get home: the flights into LaGuardia airport were all canceled.

If you live virtually anywhere in the United States, you will know that 2010-2011 has been an especially rough winter. The eastern states, from north to south, were hammered with snow, causing numerous kinds of shutdowns. So was the Midwest. There was even snow in San Francisco, definitely not the norm there. While “winter” is technically over, and temperatures in New York are a bit warmer, this only means that what would be snow has been replaced by a lot of rain. Much of this can be attributed to global warming, and specifically to the environmental impact of having a few percentage points more moisture in the air than we did a decade ago. More moisture in the air means more moisture that’s likely to come down in the form of rain or snow. And if the pattern of more rain or snow—more in frequency and more in volume—continues, it means we won’t be flying as much as we think we will in the future.

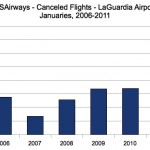

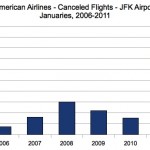

The Bureau of Transportation Statistics provides a database of flights, including those that were canceled. As you can see from these two charts, cancellations in January 2011 from two airlines at two airports were significantly higher than in the previous four Januaries: for USAirways, a high of 140 in 2011, compared with only 68 canceled flights the year before; for American Airlines, 95 cancellations in 2011, compared with a previous high of 30 in 2008. (I chose USAirways and American Airlines based on an awareness of their frequency of flights from LaGuardia and John F. Kennedy airports respectively. I selected LGA and JFK because they are my two local airports.) Sorry, you’ll have to click to see the charts at full size.

- USAirways Flight Cancellations at LaGuardia Airport, 2006-2011

- American Airlines Cancelations at JFK, 2006-2011

Sure, it’s possible January 2011 was an anomaly, the weather-and-airline-traffic equivalent of an earthquake. Only time will tell. But if this past winter’s weather continues as the norm, we may need to reevaluate our expectations about the role of air travel in the global economy, not to mention as a means of getting around. Perhaps there will be some environmental benefits as a result, though one gets the sense sometimes that it may be too late to reverse the damage.